Four Health Sector Reflections From A Month on the Ground in China

Sentiment check-in: my multi-city trip reveals the latest updates for China’s health diplomacy, biopharma innovation and high-tech transformation.

🩺 The Vital Signs series at China Health Pulse provides essential explainers on key contexts and trends shaping health in China today.

I recently returned to London after a fast-paced and energising multi-city trip across Hangzhou, Beijing and Shanghai, where each day was packed to the brim: conferences, meetings, informal debriefs — and many delicious feasts.

I caught up with friends and colleagues across government, multilaterals, academia and industry, but I also made sure to carve out time to visit hospitals and clinics. After all, high-level conversations and glossy stats can only tell you one part of how care is actually delivered. To understand a system, you have to see it move: to test a health app, queue with patients, or ask doctors what’s changed.

I left feeling invigorated, very well fed — and more certain than ever that China’s health transformations speak to a future we all need to better understand and work with, especially in a world of deepening health inequities, shifting data regimes and contested science norms.

These motivations are exactly why I started the CHP newsletter, and they also drive the core of our consulting work at LINTRIS Health: helping clients across care systems, health sectors and far-flung geographies to better understand each other, align policy, navigate markets — and build real health outcomes.

I’ve already published Part 1 of my Alibaba HQ visit in Hangzhou. This trip sparked many more insights, anecdotes and photos, which I look forward to sharing in detail.

Today’s post, however, aims to provide a sentiment check, rather than a comprehensive overview. It is centred around four themes that kept surfacing everywhere I went:

Health diplomacy recalibrated

Global health confusion

Health technology in action

China’s real confidence

1. China’s Health Diplomacy Has Recalibrated

China now sets its own terms for diplomatic health engagement, prioritising domestic policy alignment and parity over traditional Western technical cooperation models.

Two weeks ago in Beijing, I sat in a packed hall at an EU–China Conference marking 50 years of diplomatic ties. Senior Chinese officials laid out China’s global strategy on health, climate and development. What stood out wasn’t what they said, but what they didn’t: little reference to Western frameworks, and far more emphasis on China-led priorities.

That moment crystallised a pattern I’d been sensing all trip. China’s global engagement, especially in health, has entered a new phase. Health diplomacy is no longer framed around how the West can provide guidance, but around who China wants to selectively engage with, and how.

I saw this even more clearly at a closed-door briefing for the 2025 UK–China Ministerial Health Dialogue at the Ambassador’s residence, where I joined discussions alongside former colleagues from my time leading the UK Foreign Office’s health team in Beijing. The bilateral tone has shifted. While China now expects strategic alignment, it’s less clear whether it offers the same in return — particularly when it comes to mutual transparency or co-governance of global health standards.

This shift has taken time. When I took on that role in 2020, our embassy teams worked closely with Chinese health counterparts across national and local ministries. Our health programmes focused on sharing UK technical expertise — from policy design and clinical training to health insurance modelling and regulatory standards — while our trade teams promoted UK life sciences and healthtech innovation that mostly targeted inbound market access.

Then came the COVID. Health, a global public good, was swept into the turbulence of geopolitics. Mask, ventilator and vaccine diplomacy burdened the previously neutral domain of public health with strategic competition. Round-robin “origins of the virus” debates further accelerated sensitivities. The collaborative spirit that once bonded patients and populations across borders gave way to risk narratives in the name of defence and national security.

Meanwhile, institutional shifts in the West added further pressure. The UK merged its Department for International Development into the Foreign Office, cutting Official Development Assistance (ODA) to significantly narrow the scope for technical engagement. In Beijing, our £20 million UK-China Prosperity Fund health programme evaporated overnight. These painful cuts echoed patterns already underway. The US had been drawing back its NIH and CDC began scaling down China work under Trump, long before the pandemic.

And yet, even through the turbulence, I saw clearly how Chinese counterparts continued to value technical collaboration with the West, especially in areas like health economics, regulatory systems and clinical trials, where longstanding expertise was still respected and sought after. Nevertheless, bilateral collaborations had now become increasingly governed by a different logic: to serve relevance alongside China’s own standards.

These diplomatic shifts have led to commercial consequences too. In the past, regulatory approval depended on harmonisation with international standards. Today, alignment with national policy goals, including Healthy China 2030 and the 14th Five-Year Plan, increasingly determines review timelines and market access. China’s regulator, the National Medical Products Administration, has expanded fast-track reviews, but these are often skewed toward homegrown innovation. Foreign manufacturers continue to face uphill battles in data localisation compliance, pharmacoeconomic dossier submission, and real-world evidence requirements for reimbursement.

2. The Global Health System Doesn’t Know What To Do With China

Multilateral institutions lack frameworks to engage China’s dual role as funder and geopolitical competitor, creating a widening disconnect in global health collaboration.

During my trip, I caught up with colleagues who have long worked in China’s global health ecosystem. While it was lovely to return to my old team at the UN Resident Coordinator’s Office, where I’d delivered projects as a Health Advisor, and to visit friends at WHO, Gates, MSF and Ford, as well as academics and researchers at Tsinghua University and Schwarzman College. Their moods were cautious, and the more candidly we talked, the bleaker the conversations became.

Over jasmine tea in a hutong cafe, one friend despaired: “It’s hard to get anything approved that sends money directly here. This country no longer fits into global health frameworks. China makes people nervous.”

That sentiment came up again and again. China’s domestic epidemiological profile and tech capacity no longer align with traditional LMIC categories used in GBD or SDG frameworks, but its middle-income status still masks real health disparities. It is now too advanced for traditional aid, and too complex to fund easily.

China’s hybrid role as aid recipient, donor, manufacturer and geopolitical peer makes it a category-breaker in global health. This ambiguity creates risk for institutions designed around linear flows of capital or capacity-building. Policy analysts and multilateral strategists alike are struggling to adapt engagement protocols to this new configuration.

The Gates Foundation recently announced a $200 billion endowment — one of the largest in global health history. But almost none of it will go toward China. Friends at Gates described the uphill battle of justifying China-facing projects, even long-established collaborations with strong evidence of health outcomes. This tension isn’t new. I had seen it at FCDO, too, when our teams were forced to shrink down and pivot projects mid-stream just to keep them alive. Now, most institutions try to position their China engagements as external: “working with China to support others.” What remains internally is academic — technical exchanges, university partnerships and soft diplomacy workshops.

But just as other multi-laterals scale down, China’s global health visibility is ever-growing. At this year’s World Health Assembly in Geneva, it pledged $500 million to WHO over five years. Whether this is due to increased member fees or otherwise), it make China the world’s largest state donor since the US pullback. Its delegation ran side events on traditional medicine, digital health and South–South cooperation. It shared policy templates and bilateral offers with ASEAN and African Union health leaders. China is also making moves in health through global economic governance: Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank, its multilateral lender, recently committed $1 billion to GAVI, the global vaccine alliance.

As I wrote in a previous post, China is positioning itself as a health partner of choice for the Global South, offering speed, infrastructure and execution. But its model bypasses rights-based frameworks and consensus norms, raising valid concerns: opaque deals, weak civil society input and limited accountability remain consistent blind spots.

The global health ecosystem must work harder to engage China, otherwise it will misread both risk and opportunity. Streamlining bureaucracy, as the UN is now doing, is one step. Dual-track engagement strategies are another: one for conventional aid modalities, and one for peer-level partnerships like China. In addition, the private sector will play an increasingly prominent role — not only in funding where capital is lacking, but in driving actionable engagement and forging sustainable collaborations.

3. Digital is Now China’s Default Mode of Care

China has scaled digital-first healthcare delivery nationwide, integrating front-end services and back-end governance at a depth and pace unmatched globally.

In China’s urban cities, health is now digital by default, because life itself has become digital. At the airport, smart booths scanned my face to tell me what gate my flight would depart from, and mapped how to get there fastest without being asked. In the corner store, the machine automatically detected my items in seconds without needing the barcodes, and then also scanned my face to take my money through mobile WeChat pay, before I even had chance to blink.

I’ve written before that China contains multitudes, and its rural-urban, east-west and tiered city differences are very real. But the peak of where it innovates remains a sight to behold. Privacy concerns aside, the depth of integration is remarkable, and nowhere is this clearer than in China’s digital-first health delivery.

I’ll deep dive into the idea of internet hospitals in a future post, but the core principle is simple: all services along the clinical pathway— from consultation to diagnosis to prescription and reimbursement — are transitioned frictionlessly from offline to online. And this is not limited to elite urban hospitals. During this trip, I visited not only public and private tertiary facilities, but also local community clinics and township health centres. Every single one had some form of digital cloud service integrated with patient access.

Community care has improved too. In Beijing’s Ritan Park, once part of my daily commute, I paused at a new outdoor gym tucked beneath gingko trees. Elderly residents and children activated digitised machines via touchscreens, and their motion, resistance, and stats were logged onto a large monitor we could all check. This was a new part of the city’s public health infrastructure — prevention-first, ambient and completely free of charge.

When I met with the deputy director of the Beijing Municipal Health Commission, he proudly told me how the China’s digitisation efforts have transformed not just front-end care, but back-end governance across the country. The National Healthcare Security Administration (NHSA), for instance, now tracks the prescription and dispensing of every medicine box nationwide: who prescribed it, who received it and how that all compares to national trends.

Piloted only since April last year, these “drug traceability codes” had already reached 95% coverage by this January. This incredible data backbone now underpins large-scale population health analytics, pharmacovigilance and fraud detection across China: the sort of real-world evidence ecosystem that most other nations can still only dream about.

This whole-scale digital mindset was echoed at the JPMorgan Investment Summit in Shanghai. Panels brimmed with shiny examples of AI-powered diagnostics and smart precision medicine. As Unitree’s robot dog cartwheeled onstage, and MagicLab’s (rather terrifying) humanoid robot served ice creams in the hallway, executives stressed how China’s regulatory environment now enables clinical deployment of tools that remain stuck in pilot elsewhere. For many wide-eyed attendees, especially those visiting China for the first time, this was a profound reality check.

Of course, digital doesn’t mean seamless. I was turned away from one Shanghai hospital I visited, simply because appointments could only be booked online. Though I stood at the front desk, ready to pay and register, the staff couldn’t override the system. At some restaurants, internet lag made browsing e-menus difficult, but there were no paper alternatives to the digital scroll. At the airport, I even saw one of Unitree’s robot dogs again, lying askew in a tech store. The assistant told me its battery had run out: just another dystopian scene.

In China, convenience is defined less by individual comfort, and more by system-wide optimisation. That’s the cultural, societal and political tradeoff. Macro-efficiency over micro-usability, and seamless aggregation over fragmented choice: patients have to adapt. In the UK or US, even suggesting shared care records triggers privacy uproar. In this country of 1.4 billion, AI is already a daily expectation.

China is now the world’s largest testbed for digital-first delivery, and through full-stack government roll-out. The implications are enormous for health access, data governance and system design. But what barriers will surface? What models will last? No other country has scaled this fast or this wide. Regardless of whether others adopt China’s blueprint (for reasons of feasibility, privacy, or political trust), we should all be watching closely for what comes next.

4. China’s Confidence Is Now Firm. The Real Opportunity Lies in Translation

China’s innovation ecosystem is now solidly self-assured and increasingly outward-looking, but global impact depends on navigating translation risks, whether regulatory, cultural or systemic.

Confidence was the most palpable shift I noticed this time. I’ve spent my life and career traversing China and the West, but on this trip, the mood was truly new: a mixture of assuredness and ambition that I had not felt before.

Hangzhou, my home city, pulsed with it. DeepSeek and the “six little dragons” rule the narrative here in China’s thriving innovation nucleus. At Alibaba’s campus and across West Lake, tech pride has replaced tech catch-up. And in Shanghai, at the JPM Summit, I gave up trying to tally how often “the DeepSeek moment”, as they called it, was referenced, because every speaker did so. Chinese executives cited it as proof of national capability. Foreign investors benchmarked against it.

One said plainly: “We’re proud to be Chinese. We are no longer low-quality. Now innovative and competitive, we are at least equal, or even ahead.” Rest of the World reporting recently captured this too: DeepSeek’s success is “giving the people coming in the wave behind them more confidence to just be themselves. It’s OK to be Chinese overseas.”

This isn’t just rhetoric. China’s innovation engine is now self-propelling. In healthcare, the pipelines are strong: from AI diagnostics to connected devices and novel therapeutics. Many firms are actively exploring or already landing in global markets. As I’ve written before, biotech is one of the clearest sector examples.

And China’s confidence now extends well beyond tech too. One JPM investor proclaimed boldly onstage: “Chinese people can withstand hardship to help their country thrive, far more than Americans could. That’s why China’s economy will stay strong even if the US doesn’t.” The room may have laughed that day, but this sentiment reflects a solid and growing national resilience. Nevertheless, these narratives gloss over many existing risks: demographic decline, youth unemployment, uneven capital flows and tightening external scrutiny, to name a few.

Indeed, this confidence has persisted even under the current and very significant geopolitical strain. Tariffs, capital controls and talk of decoupling were discussed openly, but the mood remained relatively steady when it came to the China side, with many truly believing China’s system is now robust enough to absorb whatever shocks may come.

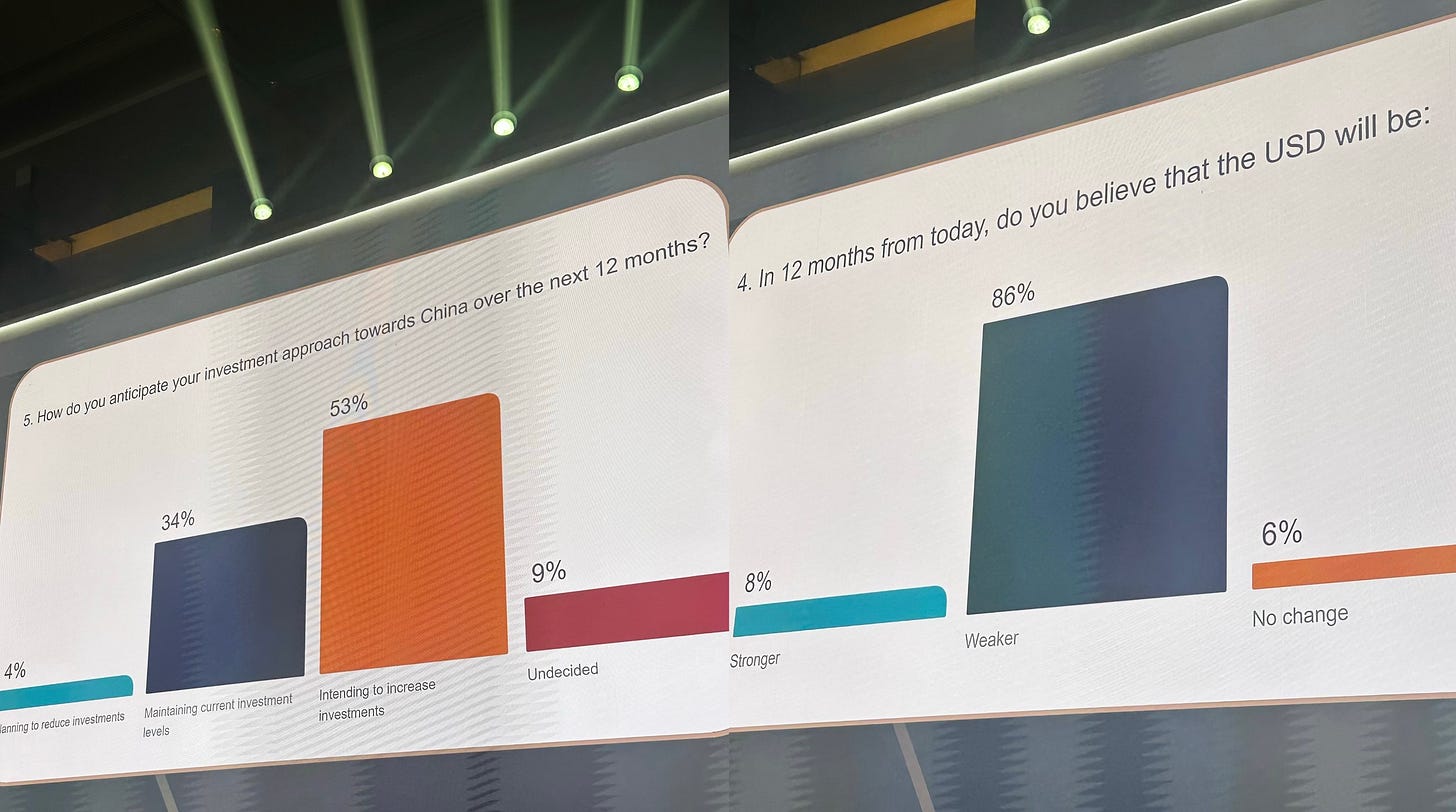

On day 1 at JPM, a live poll of the 3,000-strong audience of lead investors and global executives, showed that 53% of attendees planned to increase their investments in China, with only 4% planning to reduce. In contrast, 86% predicted the US dollar would weaken within a year. The contrast in sentiment was hard to ignore.

Of course, confidence doesn’t equal impact, and innovation doesn’t always mean export-ready. There are still many challenges across borders, from IP protection and trial transparency, to GMP standards and clinical validation in diverse populations.

Though tariffs are on pause (see my previous post), the US remains embroiled within the competition narrative, to its own detriment. Potential restrictions on Chinese student visas and growing academic distrust mean fewer researchers, fewer joint programmes, fewer human bridges. This loss cuts both ways. For the West, it’s a missed chance to tap into Chinese breakthroughs. And even for this newly confident China, it means fewer partners who understand how global health systems really work. Finally, for global health overall? It’s a loss of diversity, insight and long-term collaboration.

Final reflections

I left China feeling energised and certain that I would return soon again: being on the ground is more crucial than ever for working with this vast nation on health.

A few hours after I landed back in London, I headed straight to the London Business School’s 2025 China Business Forum, where I spoke on a panel about China’s health innovation and access. It was invigorating to share what I’d just seen on the ground — from digitised infrastructure to AI-enabled policy platforms — and to contrast it with the UK’s NHS and British biopharma, as described by my brilliant fellow panellists. That hour of collective exercise was incredibly exciting, because we translated across systems in real time together. It represents a microcosm of what’s most urgent now.

The future of global health won’t just be defined by who innovates fastest, even if China is racing ahead with confidence. It will be shaped by who can connect across borders, systems and worldviews.

I’m more motivated than ever to keep building bridges, and to keep my finger on the pulse here at CHP: diagnosing the symptoms and sharing the latest on this evolving landscape.

🩺 The Vital Signs series at China Health Pulse provides essential explainers on key contexts and trends shaping health in China today. Today’s post offers four key takeaways from my trip to China in May 2025.

Digital drug tracing was likely accelerated because of that notorious case of NHSA fraud in Dongbei. IIRC it was related to DEEJ or some type of TCM product that people managed to swipe 60x through the system.

I’d be curious to know how Chinese therapeutics companies are thinking about geographic expansion. As we’ve discussed, currently western companies are in-licensing Chinese discovered drugs at pace. But perhaps China Inc wants to expand into Europe/US if possible. Thoughts?